Pat Pesce is one tough guy. The former NYPD detective worked private security at Rockefeller Center after he retired from the force in 1998, then was enlisted by the center’s owners, Tishman Speyer, to be a driver for their executives and VIPs. Needless to say, the former cop has seen a lot over his career, and has gotten himself out of some difficult situations. But recently, the painful condition known as trigeminal neuralgia almost did to him what no job had ever done: take him out of the game. Fortunately, Pat found a world expert in his condition in Dr. Philip Stieg at NewYork-Presbyterian and Weill Cornell Neurological Surgery, and he is back to living a pain-free life with his family.

It began without warning in 2015, shortly after Pat began driving for Tishman Speyer. “I started experiencing this sudden, excruciating pain in the side of my face and the top of my head,” he recalls. Pat may be tough, but the pain was like nothing he’d ever experienced before, practically immobilizing him when it would flare up. He feared that an attack that started while he was driving could be catastrophic; for the first time in his life he thought about retiring for good. Seeking treatment, Patrick made an appointment with his neurologist, Dr. Matthew Fink at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center, who diagnosed him with trigeminal neuralgia.

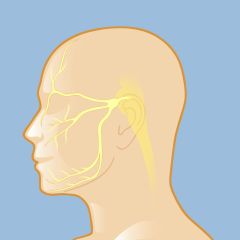

Trigeminal neuralgia is a condition of the fifth cranial nerve, also known as the trigeminal nerve, which transmits signals between the brain and the face, eyes, and teeth as well as the muscles that control chewing.

Trigeminal neuralgia is not a life-threatening condition, but the severity of the pain can make it feel that way: it’s been described as an electrical shock, a burning sensation, or a stabbing pain. Some have even called it “the suicide disease” for the level of desperation sufferers feel. The source of the pain is the trigeminal nerve, which transmits signals from the brain to the eyes, face, teeth, and the muscles that control chewing. The culprit might be a tumor that’s pressing on the nerve, or a condition such as multiple sclerosis, which damages the protective sheath on the nerve. Most often, though, the cause is a blood vessel that is compressing the nerve. Whatever is bothering the nerve, the pain is intense — even a whisp of wind, putting on a scarf, or eating can set it off.

“Dr. Fink gave me medication, which worked for a while, but after some time it wasn’t working as well as it once had,” says Pat. “I’m a tough guy and I can handle pain, but it got to the point where I couldn’t leave the house. It was happening too often and too intensely; it was interfering with my quality of life.” Dr. Fink referred Pat to his colleagues at Weill Cornell Medicine Neurological Surgery for evaluation, to discuss whether a surgical solution might be appropriate.

“Because trigeminal neuralgia is not life-threatening, the priority is pain management,” says Dr. Stieg, the Margaret and Robert J. Hariri, MD ’87, PhD ’87 Professor of Neurological Surgery and Chair and Neurosurgeon-in-Chief of NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “Medication and radiosurgery can help, and for some patients these solutions can bring the pain down significantly. But in cases like Patrick’s, the pain can outpace those treatments and can become more constant. As time goes on, the episodes occur more frequently, and the pain becomes more debilitating.

“There are several options we have to offer to patients when medication is not working,” adds Dr. Stieg. “The important thing for us is to get to know the patient individually, to determine the best course of action. We have a range of treatments available, from noninvasive to minimally invasive, to open surgery, and we work with the patient to decide which path to follow.”

Patrick learned more about his options, which included radiotherapy treatment with the Gamma Knife, radiofrequency lesioning with heat, and surgery.

“I met with [radiation oncologist] Dr. Jonathan Knisley and [neurosurgeon and stereotactic radiosurgery expert] Dr. Susan Pannullo, who could perform a Gamma Knife procedure,” says Pat. “But the results wouldn’t take effect until a month or two after the procedure and I couldn’t wait that long. By this point it was hard for me to eat, brush my teeth, or even touch my nose. My only respite was sleep, but even then I had to sleep upright with an ice pack at the ready. In between Dr. Fink’s medications, I was taking Benadryl and Tylenol to help knock me out and let me sleep a couple of hours.”

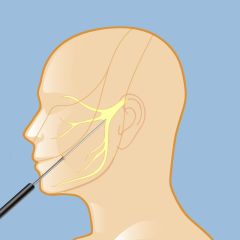

In RFL treatment, a neurosurgeon uses high heat to destroy only the pain portions of the trigeminal nerve, leaving other sensation intact.

After talking with Dr. Stieg about faster-acting approaches, including surgery, Pat decided to first try a nonsurgical radiofrequency lesion (RFL) procedure with Dr. Michael Kaplitt. RFL uses high heat to destroy the pain-sensing portions of the trigeminal nerve — it worked, but the pain eventually returned.

Everything came to a head while Patrick was at a family gathering in Brooklyn. “I pushed myself to go, to keep myself distracted,” he says. “I sat down across from my brother and I tried to bite into a slice of pizza. He saw the unbearable pain on my face, and I told him that I had to leave. That’s when I made the decision to sit down and meet with Dr. Stieg.”

“When Patrick came into my office, he was in pain not just physically but emotionally,” says Dr. Stieg. “When I speak to patients dealing with trigeminal neuralgia, it’s understandable: the pain is intractable. And it’s understandably dispiriting for the pain to keep returning — even after regimens of medicine and RFL. But this is something we specialize in here — I was confident that a microvascular decompression procedure would get us the right result. I knew he would get out of this fine.”

“When I met with Dr. Stieg, I was in no shape to engage in a conversation,” recalls Patrick. “I broke down, and I couldn’t discuss it. It was embarrassing and hurtful. But when he said I was going to be fine, I got emotional. I put myself in his hands. Throughout the course of my life, I’ve experienced different pain. I’ve taken falls, been in car accidents, broken my legs, gone through different operations. It was nothing compared to this. It knocked me down to where I couldn’t go any further. We scheduled the surgery for December sixth. I was ready to do this.”

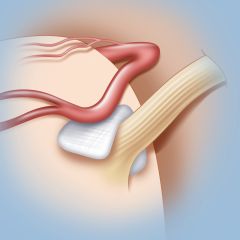

Microvascular decompression surgery for trigeminal neuralgia

“In contrast to the radiofrequency lesion that Patrick underwent, microvascular decompression requires a small incision,” says Dr. Stieg. “We go to the side of the face where the pain is and make an incision behind the ear, which exposes the trigeminal nerve. From there, we deal with whatever is making contact with the nerve. In Patrick’s case, we moved three blood vessels that were compressing the nerve, and placed a small pad of Teflon tape to block any contact with the nerve.”

“After the surgery, it felt like a rebirth,” says Patrick. “I could sit down and have a meal. I could scratch the side of my nose. That feeling like there was an icepick behind my eye, the pain in the top of my head. Gone. The nurses and the doctors were all over me — I was blessed to be in their care. And blessed to be out of the hospital two days later.”

Now 74, Patrick is pain-free and happily spending his retirement with his wife and his family. Old habits die hard, though — Patrick is back to driving a VIP: he picks up his two-and-a-half-year-old great-granddaughter.

For anyone going through this, Patrick offers some advice: “Please don’t hesitate as long as I did. Get the right care and be comfortable with your physician and your neurologist. I was fortunate enough to know Dr. Fink, who put me in touch with Dr. Stieg and the doctors at Weill Cornell Medicine Neurological Surgery. They saw the urgency and immediacy of my situation. When these doctors came along, I saw them as the light at the end of the tunnel. My pain was intense and they all took me by the hand. They were all amazing.”

More about trigeminal neuralgia

Illustrations by Thom Graves, CMI