An oligodendroglioma is usually diagnosed after an individual notices symptoms and has been referred to a neurologist, a doctor who specializes in diseases of the central nervous system.

A diagnosis of this brain tumor begins with a thorough physical exam during which a neurologist will ask about symptoms such as seizures, persistent headaches, vomiting, or other indications of pressure inside the skull. Questions to assess the individual’s mental function will likely be asked as well. The neurologist will also ask about an individual’s medical history, including past illnesses and treatments, as well as family history. The neurologist will check reflexes, balance, coordination, and muscle strength, along with hearing and vision, for abnormalities, and will look for swelling or protrusion at the back of the eye.

If the neurologist suspects a brain tumor, imaging tests and other diagnostic tests will be ordered to confirm and provide details about the tumor type, size, location, and speed of growth.

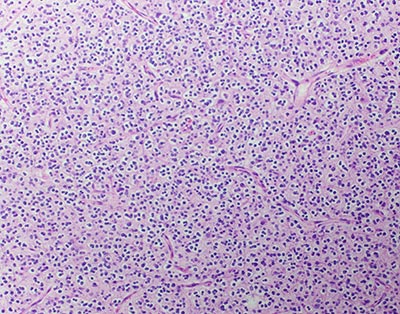

One of the most important diagnostic tests for an oligodendroglioma is a biopsy, which will be done once an oligodendroglioma is suspected on imaging. While a biopsy is part of the removal of tumor, sometimes only a biopsy itself is possible. In a biopsy procedure, a neurosurgeon will insert a long, thin needle into the tumor to withdraw a few cells. The cells are then looked at under a microscope to examine the characteristics of the cells, and a biomarker test may be called for. This is because current research suggests the importance of identifying particular gene changes or biomarkers (molecules) to confirm oligodendrogliomas. In addition, it may predict how an individual will respond to different treatments, which will assist in planning appropriate and effective next steps.

Since oligodendrogliomas are the focus of much research, learning specifics about the composition of the brain tumor can also indicate whether a person is suitable for a particular clinical trial.

More about biomarkers: Research on biomarkers has revealed a certain gene mutation that informs treatment options for an oligodendroglioma. Each cell in our body has 23 pairs of chromosomes, which carry genes from each of an individual’s parents. It has been discovered that chromosome numbers 1 and 19 in some tumor cells of this type can have a section missing. This specific alteration is associated with an improved outcome when chemotherapy is used. The 1p/19q test, as it’s called, is now used to evaluate treatments for people with certain types of tumors.

Imaging tools:

A CT scanner relies on sophisticated X-ray devices connected to computers. It may be used to get a quick view to see whether or not there is a brain tumor; it can also reveal whether there are calcifications in the tumor, since many oligodendrogliomas have some calcification.

An MRI uses a strong magnetic field and radio waves to create detailed images that reveal the location of a tumor and which parts of the brain are involved prior to surgery. Sometimes an MRI with contrast enhancement is performed; “contrast” means a special dye is injected into an individual’s blood vessels to reveal tumors.

Imaging tests of other parts of the body are not usually needed since oligodendrogliomas do not typically spread outside the central nervous system.

Treatments for Oligodendrogliomas

A neuro-oncology team at a major medical center will make a recommendation for the best treatment for an oligodendroglioma based on the type, grade, size, and location of the brain tumor, whether it has spread, the results from the biomarker tests, and the overall health and goals of the individual. Different treatments are often used in combination and require a multidisciplinary team of experts: neurosurgeons, neuro-oncologists, radiation oncologists, neuropathologists, and other specialists. In some cases, if a tumor is not growing or posing any threat to surrounding nerves or tissue, or if the patient is older and surgery is a risk, then monitoring may be the treatment of choice.

Reviewed by: Rohan Ramakrishna, MD

Last reviewed/last updated: August 2024