David “Smoky” Wurtzel, 91, of Windsor Terrace, Brooklyn, earned his nickname from a prep school teacher as a nod to the lit cigarette the young man always had in his hand. Smoky quit the habit 52 years ago, but he never did give up the nickname — which came in handy as an adult. “I traveled six of the seven continents for work, and a last name like Wurtzel can be impossible to say,” Smoky laughs. “So around the world my colleagues just knew me as Smoky — or in Japan, Smoky-san.”

Photography, one of Smoky’s passions, allowed him to document both his travels and his long and distinguished career as a software engineer. He cut his teeth helping develop launch vehicles on General Dynamics’ Atlas Project in the 1950s, and in subsequent years worked all over the world and contributed to the forerunners of modern technologies like GPS and artificial intelligence. Since retiring, Smoky devoted time to another passion: riding his recumbent tricycle.

David back in the 1990s, still behind the camera at past 60

When Smoky and his wife moved to Windsor Terrace five years ago, they gave up their car. “Riding my trike became a bigger part of my life,” he says. “It became my local shopping machine — I rode it everywhere: the drugstore, the grocery store, the post office, the bank. I live across the street from Prospect Park, which is a delightful place to ride. It has a hill so steep that a sign tells the rental bikes to turn away, but I just ride right up!”

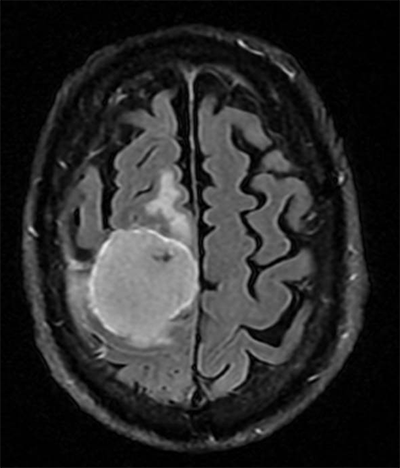

But there came a time when Smoky couldn’t ride up that steep hill anymore. A meningioma, a benign brain tumor, was causing a loss of strength on his left side.

"The tumor was initially discovered 28 years ago,” says Smoky. “At the time I decided against brain surgery. It was a pretty good decision; I had 28 years of a good life without the risk of surgery. But the tumor had been growing. As my symptoms worsened, I lost the ability to ride.”

In 2000, pushing 70, Smoky was on a ship crossing the Antarctic Circle, adding the seventh continent to his travel log.

“Ninety percent of meningiomas are benign and slow-growing,” says Dr. Philip Stieg, the chair of Weill Cornell Medicine Neurological Surgery and Neurosurgeon-in-Chief of NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “Deferring surgery, as Smoky did, can be a viable option when the tumor isn’t causing any symptoms or showing signs of growth in follow-up scans. But if the meningioma starts to grow, it can press against the brain’s nerves and blood vessels. Depending on its location, it can cause nausea, seizures — or in Smoky’s case, numbness and motor weakness in the limbs. If symptoms present, whether one, ten, or even 28 years later, it’s important to get scans done and establish a treatment plan with your doctors.”

By the time Smoky Wurtzel started experiencing symptoms, 28 years after his meningioma was first identified, it had grown considerably.

Smoky’s primary care doctor referred him to teams of neurologists, radiologists, and surgeons. “I met with all of them, and it boiled down to three choices: Do nothing, go with radiology, or opt for surgery,” says Smoky. “Doing nothing guaranteed I’d be bedridden or in a wheelchair in a year’s time. Radiation had the risk of swelling in the brain. Surgery has risks, too. I was initially opposed to surgery — not because I was afraid of it, but for the potential side effects. But, as my symptoms worsened, I lost the ability to ride for both pleasure and conditioning.”

In the end, a radiologist at Weill Cornell gave me the most useful advice, saying, ‘If you were my father, I would recommend surgery, because the risk of swelling from radiology would be worse.’”

A radiologist who didn’t recommend radiology? Smoky became more open to surgery.

“I thought I’d rather have a shot at getting better than live a few more years bedridden,” Smoky says. “That didn’t make any sense to me. So I met with three neurosurgeons. The first one said my chances were 50/50. The second put me at 30/70. Neither seemed keen to operate. Dr. Stieg did not offer any percentages. He just said that there was a good chance I’d recover and there was some chance I wouldn’t. I told him that I wouldn’t mind waking up dead. But I would mind waking up a burden to my family and myself.”

“I don’t know how to tell you what gut-level things happened that made me choose one man over another, but it just clicked with Dr. Stieg. It made it easy for me to choose him.”

“Our philosophy at Weill Cornell Medicine Neurological Surgery is to find the best approach for every patient,” says Dr. Stieg. “We never go into surgery for surgery’s sake. Even with Smoky being open to it, we had to make sure surgery was the best choice, especially at 91 years old. Our radiologist’s advice was accurate, and considering Smoky’s age, it was best to not risk any swelling. We mutually decided on a more direct approach, which consisted of a craniotomy [opening the skull] and resection [removal] of the meningioma.”

One of the things Smoky appreciated about Dr. Stieg and his team was how direct everyone was. “The best possible relationship for me, even in the face of hardship, is exchanging straight information,” says Smoky. “And from the beginning, that was the basis of my relationship with Dr. Stieg and his nurse practitioner, Elaine. Straight answers, no sugarcoating, no twist on anything. I slowly built trust with Dr Steig. Being scared doesn’t help the decision process, so I decided to keep going.”

Still a trouper at past 90, David 'Smoky' Wurtzel was awake shortly after his brain tumor surgery

“Smoky’s surgery was one we had done many times; it was a routine procedure for us, although we know it’s never routine for the patient,” recalls Dr. Stieg. “After we performed the craniotomy, we were able to access the brain and remove the tumor without damaging any vital tissue. Surgically, everything went smoothly. In the ICU afterward, he only needed Tylenol to manage some headaches.”

Smoky was on the road to recovery, and his humor and good nature seemed to aid in it.

“I remember his first words to the team after waking up were, ‘Did I make it?’” laughs Dr. Stieg. “His humor, wit, and charm helped him recover after the surgery, but I also believe that helped him recover even after a discouraging setback.”

The setback occurred shortly after being discharged from the hospital, when Smoky experienced a minor stroke. “My experience at NewYork-Presbyterian was heavenly. But the next few months were hell,” recalls Smoky. His son, Doug, echoes that sentiment. “Dad recovered very well from brain surgery,” he says. “He was doing well until that setback. The stroke brought him to rehabilitation, which he completed in March. Even after discussing it with Dr. Stieg, we don’t know what directly caused the stroke, but now we’re past that — Dad’s ahead of it, riding his trike in the park.”

Back in the park after brain tumor surgery, Smoky hits the hill on his lowrider

On one sunny spring afternoon in April, just five months after Smoky’s surgery, his family gathered in Prospect Park. Their cameras snapped away as Smoky rode past them on his trike. He’d just come down from the steep hill — just as he did before his symptoms presented. What’s more, he’d ridden one full mile. “That was the big payoff,” Doug grins. “One mile, including the steep hill.”

The contrast of where he is today compared to where he was before is not lost on Smoky. “Before the surgery I had lost a fair amount of function on my left side. I was having trouble walking,” he says. “I needed a walker and eventually a wheelchair to go to the doctor. After surgery, every day is an improvement. My family has seen tremendous progress, with me gaining back my strength. The big deal for me is that I’m riding again. I reached the one-mile mark. That was a landmark for me.”

All photographs courtesy David Wurtzel