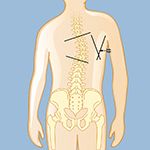

Scoliosis can be classified in many ways. One of the most common ways to classify scoliosis is by severity of the curve. Mild scoliosis is when the curve is between 10 to 25 degrees. Moderate is when the curve is between 26 and 45 degrees. Severe scoliosis occurs when the curve is greater than 45 degrees.

Scoliosis can often be clearly visible especially when it is moderate or severe. However, to establish the extent of a scoliosis and its cause, a neurosurgeon or orthopedic physician will begin by getting a complete medical history, including viewing any prior X-rays. The physician will look for asymmetries (uneven appearances) as a person sits, stands, and walks, paying special attention to the shoulders, ribs, chest, leg length, and other unusual findings, such as if the torso doesn’t appear to be evenly positioned over the pelvis, or a person’s head seems off-center. Current physical findings and measurements will be compared to prior records.

Other information will be gathered as well, including:

- Changes in a person’s height

- Family history, since some types of spinal deformities tend to run in families

- If there is bowel or bladder dysfunction, which may indicate nerve damage

- Onset of symptoms, or when the scoliosis was first noticed

- Pain, what intensifies it, and if any pain radiates from the spine itself, as well as tingling, numbness, impaired reflexes, and muscle weakness, indicating compression of nerves

- Past surgeries, as scoliosis can be a result of previous back surgeries

Scoliosis can be visualized with X-rays.

- X-rays from different angles can check for changes from past X-rays and determine progression of the curve or visualize any other bony abnormalities, fractures, and disc issues

○ Front-view full-length X-rays of the spinal column are taken as the individual stands while keeping the head erect

○ Lateral-bending X-rays may be taken from the side while an individual is standing or bending sideways or backwards to determine flexibility of the curve

Other tests may be ordered to diagnosis adult scoliosis and determine its severity and cause.

- Computed tomography (CT) is a noninvasive study that uses X-rays to produce a three-dimensional image of the spine. A CT shows more details than an X-ray and can show bony anatomy extremely well.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses magnetic fields and radio-frequency waves to create an image of the spine that reveals the discs, nerves, spinal canal, and other details that can’t normally be seen on an X-ray or CT. An MRI may also check for compression of nerve roots or spinal cord. Sometimes a contrast agent is injected into a vein in the hand or arm during the test, which highlights certain tissues and structures to make details even clearer.

- Myelograms are more invasive than CTs and MRIs as they involve a procedure to inject this dye directly into the spinal column. As such, most surgeons utilize myelograms only when the patient cannot have an MRI or has significant previous spinal hardware that inhibits the ability to visualize spinal anatomy on an MRI. Moreover, some surgeons obtain myelograms for severe scoliosis curves before their surgeries for more intricate preoperative planning.

- Pulmonary-function tests may be ordered to determine if lung function is restricted due to decreased space in the chest from the scoliosis.

- Electromyogram and nerve-conduction studies (EMG/NCS) measure the electrical activity in the nerves and muscles and are sometimes requested by scoliosis surgeons. They may identify nerve damage or nerve compression.

< Previous: Symptoms of Scoliosis

Next: Surgery for Scoliosis >