It began in 2017, as a twitch in Emma Novick's left eye. The tic wasn’t painful, but it became more persistent over time, pulling downward into her cheek. Emma was diagnosed with hemifacial spasm, which is caused by irritation of one of the cranial nerves that control movement in the face. Uncomfortable and embarrassing, the condition causes distress in those who experience it. "It became very psychological," Emma says.

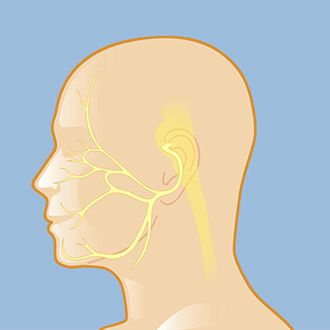

The seventh cranial nerve affects sensation across a broad area of the face — pressure on that nerve can cause the uncomfortable condition called hemifacial spasm.

In May 2020, Emma had an MRI to identify what was causing the hemifacial spasm. The source of the tic is usually compression of the seventh cranial nerve, but the MRI could not confirm that. Emma began Botox injections to try to control the spasms — and she wasn’t happy with the results.

"Botox doesn't get rid of the spasms,” she says. “It just freezes your face."

After a while, she recalls, “my face started to look completely asymmetrical.” After one of the shots, she developed ptosis, or eyelid droop. "I had my cousin's wedding a couple of weeks later, and that was a really horrible experience."

In 2022, Emma had another MRI, this time at Weill Cornell Medicine. The new scan found the culprit: an artery was compressing the nerve. Emma was referred to Dr. Jared Knopman, a neurosurgeon specializing in cerebrovascular conditions at Weill Cornell and NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital. Dr Knopman has expertise in microvascular decompression surgery, which relieves the pressure on the nerve, stopping the spasm. More than that, he understood what Emma was going through.

Dr. Jared Knopman performed microvascular decompression surgery to relieve Emma's hemifacial spasm.

"When we met him, he was so confident," Emma says. "It was really validating to hear a medical provider say that he knows that this condition affects people mentally, with confidence, meeting new people, feeling beautiful."

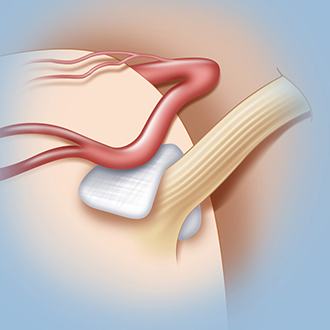

Dr. Knopman made a small incision behind Emma’s ear and gently lifted the artery off the nerve. He then inserted a small piece of Teflon to create a barrier, preventing the artery from compressing the nerve.

"I love performing microvascular decompression, because it's one of the surgeries where I can really impact the quality-of-life issues patients have," says Dr. Knopman. "It's really gratifying to see patients feel like they get their life back."

"Everybody at Weill Cornell was so kind and caring," Emma says. "I woke up from the surgery completely spasm free and have been ever since. It felt like a miracle."

It's important for patients with spasms like Emma's to get an early diagnosis, says Dr. Knopman. "The longer someone lives with this, the lower the likelihood that surgery is going to be successful," he says.

In a microvascular decompression, a neurosurgeon lifts a blood vessel off the nerve it's compressing, then inserts a small pad between the vessel and the nerve to relieve the pressure.

A month after her surgery, Emma had another special event to attend. This time she was the maid of honor at her sister's wedding — with no spasm. "I felt a lot more hope," she says.

The following year, in an email to Dr. Knopman, Emma reflected on how her life had changed. “I knew that condition was causing so much distress in my life,” she wrote, “but I didn't realize how much it was impacting me. The relief of not having a constant spasm in my face has drastically improved everything. I can sleep better, I feel more confident, I don't mind meeting new people, and it has made my job easier. This surgery felt like a miracle.”

Illustrations by Thom Graves, CMI