Read a longer sample from Shanda: A Memoir of Shame and Secrecy, or purchase the book, on Amazon.com, BN.com, or at an independent bookseller. Scroll down for links.

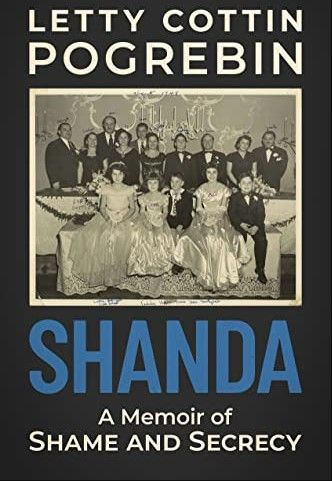

In her new book, Shanda: A Memoir of Shame and Secrecy, author and activist Letty Cottin Pogrebin exposes the fiercely guarded lies and intricate cover-ups woven by dozens of members of her extended family. The word "shanda" is defined as shame or disgrace in Yiddish. This book tells the story of three generations of complicated, intense 20th-century Jews for whom the desire to fit in and the fear of public humiliation either drove their aspirations or crushed their spirit. Ms. Pogrebin introduces her memoir with her diagnosis of a pituitary tumor, which is successfully removed by Dr. Theodore Schwartz. (Read about her experience here.) What does a pituitary tumor have to do with shame and secrecy? Ms. Pogrebin has generously shared an excerpt from her book as a view into her experience.

Chapter 1: Brain Storm

First mistake. Taking my neurologist’s call on my cell phone. At Whole Foods. In the produce department.

“We have the results of your MRI,” the doctor says, adding, before I can stop him. “It shows a growth in your head.”

I freeze, knees buckled, grab my shopping cart for support. “How big?” I ask. I’d already survived breast cancer. Where tumors are concerned, I know from experience that size matters. Stage matters. Type matters. Location matters. Everything matters.

“About the size of a small plum.”

Fate’s whimsy had stopped me at a bounteous display of apricots, nectarines, peaches—and plums, some deep purple and no bigger than a ping-pong ball, some red and speckled with the circumference of a Macintosh. The importance of tumor fundamentals had been made clear to me four years before when a mammogram revealed that I had one in my right breast. After follow-up tests and a week of petrified waiting, I learned that my tumor was malignant but small enough to be excised with a lumpectomy and treated with six weeks of radiation. It had a name, “tubular carcinoma,” which in Cancerland, is one of the “good tumors” since it seldom requires a mastectomy or chemotherapy. But in the land of the Jews, at least when I was growing up, there was no such thing as good cancer. Siddhartha Mukherjee, an Indian American oncologist, called cancer “the emperor of all maladies.” My family called it “the C-word.” Cancer was the one affliction that did not speak its name, and every Jew who received that diagnosis knew enough to expect the worst, an outcome for which centuries of Jewish history and Jewish humor had prepared us.

The Russian says, “I’m thirsty. I must have vodka.”

The Frenchman says, “I’m thirsty. I must have champagne.”

The German says, “I’m thirsty. I must have beer.”

The Mexican says, “I’m thirsty. I must have tequila.”

The Jew says, “I’m thirsty. I must have diabetes.”

For those unfamiliar with our tribe’s subgroups, I should clarify at the outset that Jews come in many forms and flavors. Those whose ancestors hailed from Spain or North Africa are called Sephardim and tend to have different habits, tastes, and practices than do Jews called Ashkenazim, who came from Eastern Europe, as did all four of my grandparents. Ashkenazim, in turn, are subdivided into Litvaks (from Lithuania and Latvia) and Galitzianers (from Ukraine and Poland), the former being self-defined as cool, rational, and intellectual, the latter as warm, emotional, and funny. (Think Leonard Nimoy as Spock in Star Trek versus Fran Dresher as Fran Fine in The Nanny.) Born to a Litvak dad and a Galitzianer mom, I should be a balance of both, but I definitely lean Litvak. For us Litvaks, the brain is not just the body’s neurological control panel but also the beating heart of the Jewish soul. And the worst place to get the C-word is in the B-word, meaning the brain, which is to say, the mind. In my family, “Jews live by our brains” was as much a truism as “Jewish husbands don’t beat their wives,” “there are no Jewish alcoholics” (because we’d rather eat than drink), “as long as a Jewish man is smart, funny, and makes a living without getting dirty, he doesn’t have to be tall, dark, and handsome,” and, “as long as a Jewish woman is smart, talented, and feminine she doesn’t have to be blonde, blue-eyed, or big-breasted.”

The plum in my brain also has a name: pituitary adenoma. It, too, is one of the “good tumors,” and the best thing about it is what it is not: malignant. Not something that metastasizes to other organs. Not cancer. That litany loops through my skull like the earworm commercial for Kars for Kids. Unfortunately, however, the plum happens to be situated perilously close to my optic and facial nerves and were it to press on them, it could deform my face and leave me blind. So, it’s gotta go.

Cue the nightmares. Shaved head. Skull cracked open with a hammer and chisel. Accidentally nicked nerve. Grotesque scar. Deep furrow. Permanent bald spot. Thankfully, a different reality unfolds. My neurologist refers me to a brain surgeon who specializes in extracting pituitary adenomas, bit by bit, through the nostrils. Called “trans-sphenoidal endoscopic endonasal surgery,” the procedure leaves no visible scars, though it does alter the interior architecture of my nasal passages and leaves me with a partially open septum (the wall separating the two nostrils). After surgery, the nose on my face, never my best feature, looks none the worse for having been used as the turnpike to my brain. But I’m not out of the woods. I have double vision, so I can’t drive. My husband sees two lines running down the middle of the road, I see two sets of double lines going off in opposite directions. I can’t smell anything—coffee, garlic, a pie in the oven. My French perfume, Madame Rochas, may as well be Windex. I can’t taste anything either, including my A-list edibles, lamb chops, four-cheese pizza, walnut brownies. The aftereffects of the procedure are disorienting and distressing. Food and beverages have no flavor, only texture (wet, crisp, dense, hard) and temperature (warm, cold, tepid). This too shall pass, my doctors promise, but being someone who expects The Worst, I’m convinced my sensory losses are permanent.

When we were kids, my friends and I used to torment each other with hypotheticals: “Suppose a bad guy was threatening to kill you unless you sacrifice one of your five senses, which would you give up: smell, taste, touch, sound, or sight?” Never a fan of forced choices, I struggled mightily before opting to sacrifice touch. Now, a month post-surgery, touch and sound are my only fully functional senses until, one astonishing morning, I open the coffee canister and literally smell the coffee. I get off on the fragrance but when I brew a cup, it has no taste. Days later, again with no warning, a sip of fresh orange juice explodes in my mouth and tastes the way Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” sounds. A few weeks after that, the double lines reunite on the West Side Highway. The scent of lilacs growing in profusion along a path in Central Park overwhelms me with its intensity and the peachiness of a perfect peach almost brings me to my knees. Gratitude has long been my default, but once all five senses are in working order, I’m freshly awed by the miracle of the ordinary and the fact that each new dawn takes me further away from that surreal moment in Whole Foods when I heard the words “brain” and “tumor” in the same sentence.

What, you may be wondering, does this have to do with a memoir about shame and secrecy? A lot, it turns out.

Read a longer sample from Shanda: A Memoir of Shame and Secrecy, or purchase the book, on Amazon.com, BN.com, or at an independent bookseller.

Letty Cottin Pogrebin shares her pituitary tumor experience here: "I Assumed I'd Been Handed a Death Sentence"