Vascular specialists, who work with patients experiencing conditions and disorders of the blood vessels, often talk of the “Lazarus effect,” a phenomenon in which a patient revives after coming to the brink of death, as happens in stroke or heart failure. That's what happened to Alan Lichtenstein, whose blood flow in the left half of the brain was completely blocked and who was in some sense of the word dead (or at least perilously close to it) when doctors saw him suddenly come back. It was a profoundly moving experience for patient and doctors alike.

Alan had already had a stroke – and a major stroke of luck – earlier that evening, when he’d experienced the dizziness, confusion, and deterioration of speech that signaled a brain attack. The stroke, caused by a blood clot in the brain, easily could have claimed his life, but a 911 dispatcher called for the new Mobile Stroke Treatment Unit (MSTU) from NewYork-Presbyterian. This specially equipped ambulance is designed to get stroke victims the immediate help they need to prevent damage to the brain, and Alan was given tissue plasminogen activator (tPA, the “clot-buster”) while he was still en route to the hospital. His life had been saved. But the night wasn’t over yet.

Like all stroke patients, Alan was evaluated upon arrival in the ER to see what steps to take next. If a clot had still been present, the neurology stroke team would have called in the interventional neuroradiology (INR) team to determine if he needed emergency surgery to remove the clot. That night, it was determined that the clot-busting drug had done its job and surgery was not needed.

Several hours later, however, Alan suffered a second, and much worse, stroke. He was unable to speak or move his right arm. The neurology stroke team ordered an immediate CT scan, which revealed a new clot. It was larger than the earlier one, affecting a much larger area of his brain. With every minute that passed, his brain was being deprived of oxygen, risking irreversible damage.

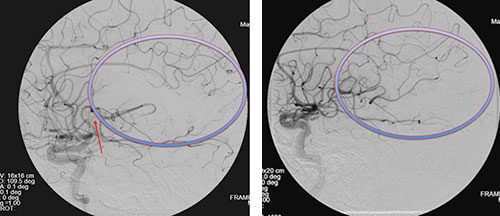

The scan at left shows the location of the blood clot (red arrow) and the resulting lack of blood flow in the circled area. At right, the scan shows restored blood flow after we removed a very large blood clot using a special clot retriever.

Alan got his second lucky break of the night when the emergency room team sent those CT scans to the INR specialist's smart phone. As it happened, the specialist was with several other members of the INR team at a nearby restaurant celebrating the graduation of the latest class of residents and fellows. No sooner had they all settled into their seats than the call – and the scans — came through. The whole team could see that this patient needed surgery to remove the clot, immediately, and they all jumped from their seats and headed over to the hospital.

Alan was in very serious condition. Not only could he not speak or move his right arm, the team knew his brain was dying, right in front of them. The part of the brain that suffers from lack of blood flow dies soon after being cut off from oxygen, and when oxygenated blood is blocked by a clot there is simply no time to spare. The clot had to come out immediately. The INR team had to act fast.

INR specialists are used to performing delicate image-guided procedures in the brain – they can insert a microcatheter in the large artery in the thigh and thread tiny tools up into the blood vessels in the brain. They do this for a number of reasons – to repair an aneurysm, to insert a stent into a narrowed vessel, even to deliver chemotherapy directly to a brain tumor – and it’s a slow and careful process. On this night, their task was to go into Alan’s brain immediately and get that clot out – a procedure called embolectomy — before his brain died. They wasted no time in getting this patient ready for the procedure.

Watching on the procedure room monitors as the radiologist snaked a special clot retriever tool up into Alan’s brain, the team held its collective breath. He was conscious, not under anesthesia, as this is a painless procedure, but he was unable to speak and was partially paralyzed. The team knew that every minute counted as the radiologist maneuvered the retriever into place.

The ruler tells the story: This very large blood clot was threatening Alan Lichtenstein's brain until the INR team removed it using a special clot retriever.

“Doing well,” responded the man who moments earlier had been unable to speak. The doctor asked him to raise his right arm – the arm that had previously been paralyzed. He raised it easily. He recovered fully within minutes and was able to talk to his wife soon.

The team could not have been more amazed had Lazarus himself sat up on the table. Alan was alive, and neurologically intact, with no significant damage from his close brush with brain death.

It’s not easy to just return to dinner after an experience like that. But the whole team did, celebrating the end of the academic year with a case that was one for the history books. Our faculty had already been proud to send these young residents and fellows out into the world, to bring their skills to patients across the country. This one last procedure was the icing on the cake – any patients out there who see one of these young neurosurgeons in the ER one day should thank their lucky stars to be treated by such talented doctors.

Best of all, Alan continues to do well. The team had returned him to his family with more life for them to live together. All in all, as a day at work goes, this was a pretty good one.

Read more about Mr. Lichtenstein’s experience in this New York Daily News article about it.