Geoffrey Donaldson, 78, is a marketing consultant who splits his time between his home on Long Island, NY, and a cabin in the Berkshires. “I used to hike a lot, but I have a condition called transverse myelitis, an inflammation of the spine. It manifests in loss of balance, leg discomfort, and pins and needles in my feet.” Geoffrey says. “These days I can still do a limited hike with the aid of walking sticks, but I mostly spend my time with my children, working, exercising, occasional 'hacker' golf, lots of ambling, and endless reading. I’m surrounded by a large family: five children, ten grandkids, all beautiful and brilliant, of course. A wife — a great mom! — that I’ve been married to for forty-five years. Most of my children live around my home here on Long Island. My wife loves it all — it’s a hubbub of activity.”

As if the transverse myelitis weren’t enough, last year Geoffrey’s otherwise idyllic life was suddenly disrupted by some issues with his left eye. “It would go dark for fifteen seconds or so at a time,” he recalls. “I saw my ophthalmologist, who was in contact with my GP, Dr. Martin Post. They said that this vision loss, called amaurosis fugax, was a symptom that something else was going on.” Geoffrey’s doctors did an ultrasound of his carotid arteries, the results of which led him to Dr. Jared Knopman, director of cerebrovascular surgery and interventional neuroradiology at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

“The gray film Geoffrey saw is a potential symptom for patients experiencing significant carotid narrowing,” says Dr. Knopman. “Carotid stenosis, as you can tell from the name, is related to the carotid arteries located on both sides of the neck. It’s where you typically place your fingers to find a pulse. Above that point, the carotid artery branches into two smaller vessels, one of which goes to the brain. When the pathway that leads to the brain is blocked or narrowed by plaque, pieces of plaque can spontaneously break off, which can lead to retinal hypoxia, thus the temporary loss of vision. Symptoms like this may resolve, but if they’re left ignored, they can lead to a significant subsequent stroke.”

“Dr. Post called me with the ultrasound results: one of my carotid arteries was ninety percent plugged, and the other was eighty percent calcified,” says Geoffrey. “I was surprised — I took next to no medications. But there were these things going on in my body that could have potentially killed me or caused some serious brain trauma. I went from thinking that I knew everything about myself to not knowing anything. I just recognized that I was lucky — I was able to have this operation that was necessary to save my life.”

Both arteries would have to be opened up, and the left side would have to be done quickly — because Dr. Knopman was about to take a much-deserved vacation with his family. “I was leaving on Friday,” says Dr. Knopman. “We’d have to shift things around, but you can’t leave your patients’ well-being hanging in the balance.”

“I instinctively felt a connection with Dr. Knopman,” says Geoffrey. “I was just appreciative of the fact that he would get my surgery done on such short notice. It was beyond belief to me that he could be so gracious and considerate for someone he’d just met. Meeting him in person, I found him to be honest, gracious, and compassionate at the same time. And because of that, I was feeling pretty comfortable leading up to the surgery.”

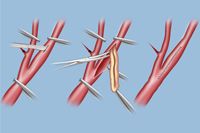

In a carotid endarterectomy, the blood flow is temporarily clamped off, then a vertical slit is made in the blocked artery. After the blockage is removed, neurosurgeons reconstruct the vessel wall and close up the artery.

Geoffrey was cleared to return home the very next morning. “One of my kids drove up and I walked out by myself — I was good to go. At home, I was somewhat limited physically, but nothing to the point of being bedridden. I was able to take care of myself. No dizziness, nausea. My family gave Dr. Knopman updates — he called me from his vacation to check on me,” laughs Geoffrey. “With the seriousness of the situation, I’d have expected to suffer more, but I didn’t.”

Three months later, Geoffrey returned to Dr. Knopman to have another endarterectomy, this one on his right carotid. “I’d been taking it easy between the surgeries,” says Geoffrey. “But a month after the second operation, I went back to the gym. Today, I’m back four times a week. I returned to doing physical therapy for the issues stemming from the transverse myelitis. My recovery period, for me, didn’t require anything serious or restrictive. I felt the same post-op as I did pre-op. But my carotids are clean and that’s one thing off the table.”

Looking back, Geoffrey is appreciative of the care he received. “With this, I’ve had another great experience with NYP and its doctors,” he says. “I go back a long time with NewYork-Presbyterian, back to when it was still New York Hospital. Fifty years ago, my mother had some strange bacterial disease that she caught after traveling. They figured it out at NYP, and she lived for another twelve years. They saved her life. Since then I’ve had a long, positive relationship with the doctors here. They’ve saved my life repeatedly, and Dr. Knopman is in that league of great doctors that populate this organization.”

More about carotid occlusive disease

More about Dr. Jared Knopman