Chaniya Wigfall, 20, is a full-time student in Syracuse, New York. An aspiring microbiologist originally from Harlem, New York, she recently finished up a summer internship at a lab in Binghamton. In her spare time, she jokes, “I like crocheting, shopping. I’m like an old lady!” You wouldn’t know it by talking to her, but until recently this very young lady had been dealing with headaches that threatened to derail her academic career. By being her own advocate and searching for a diagnosis, she’s now back on track — with help from Dr. Srikanth Boddu and his team at NewYork-Presbyterian / Weill Cornell Medical Center.

“I had really bad headaches back in middle school,” recalls Chaniya. “I went to the doctor and they said it was just migraines. They said, ‘Just take Tylenol, it’s nothing crazy.’ But in my senior year of high school, my headaches just got worse and worse. I went to a neurologist to see if something else was wrong. They did some scans and found a pineal cyst in my brain; they said the migraines were coming from the cyst. But when I went to a neurosurgeon, they said it couldn’t be that. I went back to the neurologist, and they put me on pills, which just made me feel worse. I felt like nothing was working and I was getting frustrated. I wanted another opinion, so I turned to Weill Cornell Medicine Neurological Surgery and asked if they could take a look at my scans.”

By this time, Chaniya was in her first year of college. She needed a solution — her headaches were having a noticeable effect on her academic performance. “I was having severe migraines and calling out of work,” she says. “School was getting worse, I was missing class, and my grades were dropping. I had bad tinnitus. My eyes were getting bad, and my doctors were giving conflicting advice on that. It was a lot.”

Chaniya first met with Dr. Jeffrey Greenfield, a pediatric neurosurgeon at Weill Cornell Medicine Neurological Surgery. “I could sense her frustration,” recalls Dr. Greenfield. “When patients are getting conflicting opinions, it can feel like there’s no answer in sight. But when we got her scans back, it was a familiar sight: pseudotumor cerebri, which is also known as idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH). I referred her to my colleague, Dr. Boddu, our interventional neuroradiologist who specializes in treating IIH and could provide additional options for Chaniya’s treatment.”

“IIH is a disorder characterized by increased pressure in the fluid surrounding the brain,” says Dr. Boddu. “It’s unknown what causes it, but if left untreated the pressure can lead to other complications: headache, vision problems, papilledema [swelling of the optic nerve] — or worse, a complete loss of vision.”

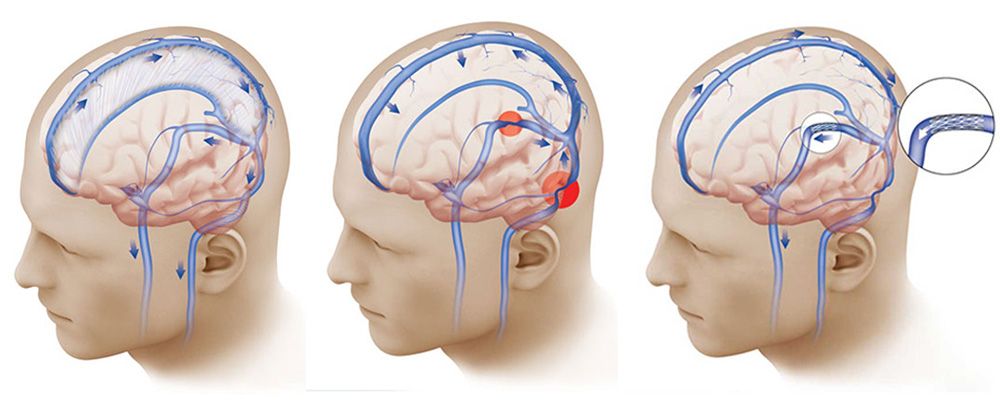

One solution, says Dr. Boddu, is implanting a shunt, which relieves the pressure in the brain. There is, however, an alternative. “The vast majority of patients diagnosed with IIH also have something called intracranial venous stenosis - a narrowing of one or more veins in the brain. Patients who have this stenosis are candidates for a minimally invasive procedure called venous sinus stenting, or VSS. When I met with Chaniya and looked at her scans, I felt confident we could relieve her symptoms.”

Normal pressure in the brain is maintained by a system that drains cerebrospinal fluid (left). In some people, a narrowing in those draining veins (red circles, center) interferes with that balance. A stent in those veins (right) can relieve the pressure.

“I remember when I first met with Dr. Boddu,” Chaniya recalls. “He called me on Zoom and we talked about my diagnosis. For so long, I’d been told that there was nothing wrong. It was like, take a bunch of pills and it’ll go away. But when I talked to Dr. Boddu, he told me he understood what I was going through and that he was going to find the problem. When he diagnosed me and talked about how he could fix it, there was nothing else for me to say — it was the first time I got a clear, definitive answer.”

“I recommended Chaniya for the clinical trial being done for VSS,” says Dr. Boddu. “Because it’s minimally invasive, we don’t have to open up the skull to address the problem - as a result, the patient has a significantly reduced recovery time. We insert a needle near the groin and utilize the body’s network of veins to thread a catheter from there to the narrowed vein in the brain. From there we deploy a stent, which widens the vein and helps alleviate the pressure as well as the patient’s symptoms.”

“After talking with Dr. Boddu, I finally felt heard after so many years. I chose to go ahead with the surgery — I wasn’t going to do anything else,” says Chaniya. “He was very transparent with everything. He’s a very quiet man, but he’s very thorough and concise. If I had any questions, he wanted to make sure I was comfortable with everything. And me, I’m on Google checking everything — he addressed every single thing I asked him.”

In April 2021, Chaniya went to NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. She hated the spinal tap, which tests the pressure of the cerebrospinal fluid, but fortunately she didn’t need it done more than once. The surgery only took two hours, and as expected, relieved her of all her symptoms.

“The surgery itself was easy,” she recalls. “When I woke up, it was a relief. But through the excitement and anticipation of it all, it just culminated in the feeling that this is what it’s like to be normal. This is how my brain’s supposed to feel. I just felt normalcy.”

Post-surgery, Chaniya is making up for lost time. “When I had surgery, it was the second semester of my first year in college,” she recalls. “I was so behind that my grades were suffering. So I had to immediately jump back into study mode. I was trying to redo what had been messed up the previous semester. I’m rebuilding and making up for it. To this day, I have no time to do anything — I’m just working. But to anyone out there going through this, get the surgery. Just do it. Unless you want to be on pills for the rest of your life. Take the road more traveled.”

More about pseudotumor cerebri

Illustrations by Thom Graves, CMI