Keith Maloney, 52, of Norwell, Massachusetts, is quite an active guy — he commutes 24 miles each way to work in Boston; spends time with his wife, Lori, and their two daughters; and regularly practices taekwondo. One day, as he was doing some of his usual warm-up positions, Keith had a brief spell of dizziness. Proactive as usual, Keith visited his cardiologist, who determined that the dizziness stemmed from a delay in blood flow as he rose from his warm-up positions. Little did he know there was a more serious problem — one which would lead him to New York City and into the capable hands of Dr. Mark Souweidane at NewYork-Presbyterian / Weill Cornell Medical Center.

Keith didn’t know it at the time, but it was a colloid cyst, not taekwondo, that had caused his dizziness. A colloid cyst is a little “pocket” that forms deep in the brain, usually filled with fluid. Colloid cysts are relatively rare, developing in only about three in a million people, and many people never even know they have one. Keith could easily have been one of those people were it not for a car accident.

Keith and Lori were picking up groceries when their car was rear-ended. The emergency room tested them both for concussions, but Keith had hit his head on the Jeep’s rollbar and had a nasty abrasion on his forehead. Because of that wound, the hospital did a CT scan to check for any internal bleeding.

About an hour later, a doctor called Keith and his wife into a small room. “The emergency room doctor wanted to speak with us,” Keith remembers, “I had a feeling it wasn’t great news.” The CT scan had found a 13mm colloid cyst located in the center of the brain.

A colloid cyst, while typically benign, has the potential to grow and block the flow of cerebrospinal fluid, which can cause sudden losses of consciousness or even death. Depending on several factors — the size of the cyst, whether or not it’s causing symptoms, or if the patient has hydrocephalus (fluid buildup in the brain) – observing and monitoring the cyst over time may be the best option. Unfortunately, the CT scan showed that the cyst was on the larger size and that Keith had hydrocephalus. Combined with the dizziness he’d experienced, a “watch and wait” approach would not be an option.

Keith Maloney and family

The neurosurgeon on call advised Keith to stay at the hospital and undergo an MRI scan to learn more about the cyst. Eager to leave the hospital, Keith declined. “We had two teenage girls and we wanted to get home, as they knew we had been in an accident,” says Keith. “I’d never heard of a colloid cyst but I heard the word ‘benign’ and I knew it could have been much worse. Life had been hitting hard — I’d lost my mother three months prior to the diagnosis. I just tried to turn my thoughts toward visualizing a positive outcome.” The doctors were wary of his decision but relented only when Keith committed to scheduling an MRI within the next couple of days.

Over the next few days and weeks, Keith and Lori did some research about colloid cysts. They learned more about the potential risks of watch-and-wait versus treatment, and how the equation has changed since the introduction of endoscopic neurosurgery. Not long ago, removing a colloid cyst in the third ventricle usually required a craniotomy (opening the patient’s skull) or the placement of a shunt to treat the hydrocephalus (leaving the cyst in place). Patients would have to weigh the risks of invasive surgery and its possible cognitive side effects against the risk of sudden death as the cyst grew. Today, with endoscopic surgery, only a tiny incision is required, reducing surgical risk and reducing recovery time.

With those new odds in mind, Keith and Lori decided to move forward with surgery, and set out to find the most experienced doctor to do it.

The neurosurgeon they originally met with recommended a craniotomy — but Keith and Lori focused on finding a surgeon who could perform an endoscopic procedure. “We were looking for the most experienced neurosurgeons, the best technology, and facilities with the best outcomes,” Keith recalls. One local hospital they reached out to said it would take eight to ten business days to get a call back. Lori, after some online searches, found Dr. Mark Souweidane in New York.

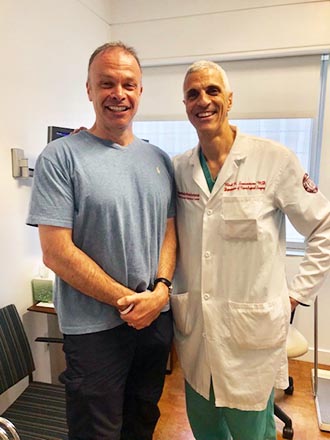

Keith Maloney with Dr. Souweidane

Dr. Souweidane is one of the world’s foremost experts on endoscopic surgery for colloid cysts, with more than 135 endoscopic colloid cysts surgeries to his name. “With the advent of endoscopic surgery, the reward now far outweighs the risk,” says Dr. Souweidane. “By partnering stereotactic planning with our surgical tools, we ensure the best location for entry. We’re able to extract the colloid cyst through a very small hole — it couldn’t be a more stark contrast to a craniotomy. Best of all, most patients return home about two days after the surgery.”

Keith and Lori submitted an online request for a second opinion, sending Dr. Souweidane the MRI scan along with the first neurosurgeon’s recommendation for an open craniotomy. They received a response the next day and scheduled an in-person appointment a week later.

Lori had been initially skeptical about the five-hour drive to New York – Boston certainly has great doctors and hospitals – but Dr. Souweidane’s experience and skill trumped the distance between them. “Once we met Dr. Souweidane we discovered that patients come from all over the country and the world to see him,” Keith notes. When friends asked why he was going to New York for surgery, with Boston’s capable surgeons in his own backyard, he replied, “I wanted access to the most experienced neurosurgeon and I needed to feel comfortable with him.”

Keith asked Dr. Souweidane the most important thing he had learned after performing all those endoscopic surgeries. Dr. Souweidane confidently replied, “I’ve learned there’s a certain way to curl to extract the roots of the cyst.” Keith says after hearing that level of technical detail, he knew he’d found the right surgeon for the job. “With all of Dr. Souweidane’s experience, he was the neurosurgeon I wanted. If everything was to go right, I wanted him there. If something were to go wrong, I wanted him there.”

Less than a month after that initial consultation, Keith and Lori drove to New York for the surgery. Keith’s dizziness, now with headaches, escalated in the last weeks before surgery — likely due to both the hydrocephalus and anxiety.

The procedure took about three hours, and by 10:30 am Keith was in the recovery room. As he regained consciousness, he tried to recall his taekwondo patterns. “I told Dr. Souweidane that I’d know he did a good job if I could remember my taekwondo patterns. I remembered them all,” Keith says. “He later stopped by and I thanked him for saving me. It was the only time I teared up in that whole process.” Keith happily recalls.

Keith was back at work full time just a month after surgery, and within three months he had resumed taking taekwondo class twice a week. Eight months later he participated in his first taekwondo tournament along with his oldest daughter.

After his recovery, Keith joined the Colloid Cyst Survivors group on Facebook. “I see several people struggling who have had multiple craniotomy brain surgeries, and people having difficulty finding experienced neurosurgeons,” Keith says. “I tell them, based on my experience, if you are looking for the most experienced neurosurgeon for colloid cyst removal, combined with the best outcomes and overall patient experience, they need to see Dr. Souweidane at Weill Cornell Medicine!”