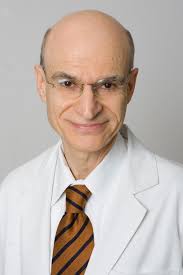

I was deeply saddened to learn of the recent passing of Dr. Ronald Brisman, another neurosurgeon lost to Covid-19. Dr. Brisman, like Dr. Jim Goodrich, the pediatric neurosurgeon who recently passed away, was a product of The Neurological Institute training program, which was then part of Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center, now NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital. Dr. Brisman stayed on to work at Columbia and was one of my attending physicians when I trained there from 1993-1999.

Dr. Brisman, or “The Bris,” as he was known to the residents, was an expert in treating a disease called trigeminal neuralgia, a painful irritation of the face that can be so excruciating it prevents eating or talking. Trigeminal neuralgia, also known as “Tic Douloureux” or “tic,” causes a pain so severe that even a slight brush of wind on the face can trigger spasms of lancinating pain so horrible as to render a patient, in years before effective treatments, willing to take their own lives to arrest the sensation. In the modern era, we can treat this disease with medication and when the medication fails, there are surgical options.

The treatment of trigeminal neuralgia provides a reflection of the evolution of the field of neurosurgery itself. Early treatments were mechanical, consisting of injections of toxic chemicals or compression of the nerve with balloons through needles inserted in the face, guided with x-rays. With the evolution of modern microsurgery and high-resolution imaging, the cause of tic was soon discovered to be a small blood vessel compressing the nerve.

Soon another treatment was developed by a pioneering and brave neurosurgeon named Peter Janetta called a microvascular decompression. While very effective, the surgery required drilling holes in the skull; it is considered very safe but has associated small risks. In the modern era, with the introduction of computers, image guidance, robotics and stereotaxis to neurosurgery, a new treatment became available in which high doses of radiation can be applied focally to the trigeminal nerve to alleviate the pain.

I mention all of this only because Dr. Brisman’s career followed the course of the treatment of tic. He was first a specialist in the percutaneous needle treatment, then the craniotomy, and finally the computer-guided minimally invasive radiation treatment. Like any great neurosurgeon, he was not locked into one treatment modality but rather wished to offer his patients the best therapy, with the greatest effect and the least risk.

There are very few neurosurgeons alive today who are such a world expert in a disease that they can fill their entire career with the treatment of only that one entity. Dr. Ronald Brisman was just such a neurosurgeon. He was such an inspiration that two of his sons went on to pursue neurosurgery, which I am sure filled his father with unending pride. I am lucky enough to be friends with both of them.

The world has lost a unique individual with the passing of Dr. Brisman, and I am sure his patients and the entire tic community will be hard pressed to find another doctor who will devote their entire career solely to the treatment of their disease.

Last month, even before any of us fully grasped the enormous impact the pandemic would have on health care, I spoke with the Neurosurgery Podcast about the dramatic impact of Covid-19 on New York neurosurgeons.

Neurosurgery Podcast · COVID 2020 - Chapter 5: The Big Apple