As a PA in Neurosurgery at NewYork-Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medicine, I typically spend my days assisting neurosurgeons in the operating room and taking care of our inpatients before and after surgery. I have been trained in CPR, having taken the hospital’s provided and required Basic Life Support (BLS) and Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) courses, but it is not something that I have often been called on to do. In fact I had only ever used it once before, until I was recently called into action — of all places, on an airplane flight.

I was on a plane returning to New York from Ireland, where my family had taken my father’s ashes home to bury. As you might imagine we were feeling reflective, thinking about life, death, and what really matters in life. We were all pretty tired, and eager to get back to the States.

About an hour out from landing, there was an announcement asking if any doctors on board would make themselves known to the flight crew. My sister and brother looked at me, and I looked around for airline staff but I didn't see anyone. Then I saw the crowd in the aisle about 15 rows in front of mine. I went up and excused myself to some of the people in the crowd so I could get closer, and a flight attendant asked was I a doctor. I said no, I am a Neurosurgery PA, and she gestured me forward. I’m not even sure if she understood what a Neurosurgery PA was.

A man was lying in the aisle with one person pushing on his chest and someone else at his neck trying to find a pulse. I told them to stop compressions while I checked for a pulse – there was none, so I started compressions. I shouted for anyone else who was able to assist in CPR to step up. A nearby passenger was willing to give mouth-to-mouth (surprising, since many people aren’t willing to do that these days, which is why there’s been a new effort to teach hands-only CPR. After I did 30 compressions he delivered two breaths.

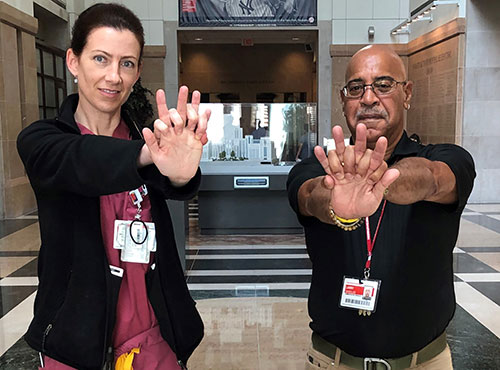

We got into a cycle of three people rotating through compressions – doing compressions is physically taxing, and I wanted to be sure we maintained our ability to keep going – and I also rotated with the man providing breaths. Two other passengers volunteered to help with compressions, but they were ineffective so I removed them from the line-up to maintain high-quality CPR. In my head I kept hearing the voice of my amazing CPR instructor at NewYork-Presbyterian, Larry Wheeler (“allow for chest recoil,” “ensure chest rise,” and my favorite, “he’s dead, you can’t hurt him!”). I was grateful for having had Larry as my instructor throughout my years of taking BLS and ACLS at NYP.

Beth Higgins and her CPR instructor, Larry Wheeler, show off their hands-only CPR form

Beth Higgins and her CPR instructor, Larry Wheeler, show off their hands-only CPR formA flight attendant brought out an AED (an automated external defibrillator, which can shock a heart back into rhythm), and a very pregnant nurse stepped up to ask if she could help. I asked her to manage the AED (she was fabulous monitoring rhythm), and I told the crew that we needed to land as soon as possible.

We gave three shocks with the AED during ongoing CPR, which got us to ROSC (return of spontaneous circulation). Amazingly, the patient resumed consciousness and was able to say where in Ireland he was from. He then went into vfib (ventricular fibrillation, an erratic heart rhythm that doesn’t pump blood) and we resumed CPR. We delivered three or four more AED shocks, and we got to ROSC again. The patient was speaking, answering questions, and following commands.

We all braced in position for landing, with the patient still on the aisle floor and us gathered around him. EMS was waiting for us on the ground and whisked him off to the hospital, still awake, still speaking, still responding to instructions. My hastily assembled crew of volunteer life-savers sat back in disbelief (and pain — I was drenched in sweat, had rug burns on my knees, and my abs were killing me!), amazed that we had somehow come together in the narrow confines of an airplane aisle to bring a man back to life.

I later discovered that the nurse who did such a great job with the AED is Michelle Healy, who as it turns out lives not far from me. I wish I knew the names of the other people who stepped up that day – an amazing group of strangers came together, and we coordinated well as a team when it counted most. I don’t know much about the man whose life we saved, either, but I’m sure he knows what a remarkable experience we all went through together. I have since learned that he survived his ordeal and was discharged from the hospital he was taken to. I hope he is home with his family now, enjoying his second chance at life. The thought of that makes me so happy — it’s worth the rug-burned knees and sore abs.

Mostly I hope that someone reading this story is inspired to sign up for CPR training. When the heart stops pumping, brain damage starts in minutes. In just the short time it took to retrieve the AED and get it started, and in the period of vfib between shocks, our little team of volunteers kept a man’s brain alive and gave him a chance of living out his life. Anyone who is ever in a position to help – and it can happen anytime, anywhere – has an amazing opportunity to save a life. Hands-only CPR allows anyone to participate without having to do mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Learn how today!

Update August 9, 2019: Beth was named Employee of the Month for July by NewYork-Presbyterian. She was honored at the hospital-wide Town Hall meeting and presented with her award by Dr. Katherine L. Heilpern, senior vice president and chief operating officer of NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.