Our hearts go out to Teddi Mellencamp and her husband, Edwin Arroyave, whose five-month-old daughter, Dove, will soon undergo surgery for lambdoid craniosynostosis. We know how frightening it is to find out your child needs surgery – we are parents as well as surgeons, so we know this particular anxiety from both sides. As surgeons specializing in corrective surgery for craniosynostosis, we bring a very specific point of view to this discussion.

Dove was diagnosed with craniosynostosis, which is a rare condition to begin with, occurring in only one out of every 2,000 to 2,500 births. It can take a few different forms, and lambdoid craniosynostosis is the least common. Fortunately, there are surgical procedures that treat this condition, and in the hands of an experienced craniofacial team most children do very well with no lasting effects of this diagnosis.

Why Is an Infant’s Head Different from an Adult’s?

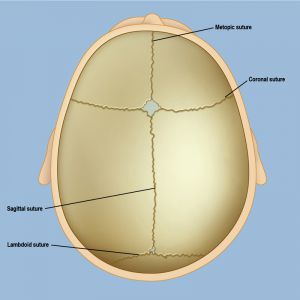

A baby’s skull needs to be small enough to fit through the birth canal, but still be able to accommodate extremely rapid brain growth over the following two or three years. This is possible because an infant’s skull is not one solid bone, but several individual plates held together by fibrous intervening tissue known as sutures. These are not the kind of sutures you might get in the emergency room for a deep cut, but they do perform a similar function: they temporarily hold adjacent pieces together while the skull grows and slowly fuses, or hardens, over time.

These sutures hold the plates in position but allow them to shift and overlap during childbirth to allow passage through the birth canal. This molding during delivery can contribute to “ridging” and other head shapes immediately after birth that usually resolve quickly as the plates shift back into position. As the brain grows, the sutures allow the skull to enlarge and accommodate this brain growth. The “soft spot” on a baby’s head is where four of the bone plates meet.

Once the most rapid stage of brain growth is complete, the sutures slowly close and the skull fully ossifies, or hardens. This process begins at different times for different sutures. For example, it can be normal for the metopic suture, at the forehead, to close at only a few months of age, while the sagittal suture can be visualized on CT scans in teenagers. This is a dynamic process that varies for most patients based on additional factors, however no suture should be closed at birth.

What Happened to Dove?

In some children, one or more of the sutures fuses too soon, known as craniosynostosis. This is typically apparent at birth, however it can take a few weeks for the findings to become noticeable enough to raise concern. When a suture has fused too early, the brain continues to grow but the skull cannot expand uniformly to accommodate this growth. As the brain grows, therefore, the bone plates of the skull expand in the directions that are available from the remaining open sutures, resulting in predictable and diagnostic head shapes based on the involved fused suture.

The most common form of craniosynostosis is sagittal synostosis in which the suture at the vertex, or top of the head, fuses too soon. With the skull unable to grow side to side, the child develops an elongated head shape. When the metopic suture in the middle of the forehead is involved, fusion results in restriction of side-to-side growth of the forehead, with a subsequent triangular shape of the head. When a coronal suture is involved at either side of the forehead, this results in elevation of the eye on one side, depression of the eye on the other side, and flattening of the forehead on one side. In Dove’s case, it was one of her lambdoid sutures at the back of the head that fused early. When this occurs, the back of the head assumes a “windswept” appearance and the ear is pulled down on the affected side.

Since one of their older children had torticollis as an infant, it’s not surprising that Dove’s parents assumed the head shape that was emerging in their new baby was similarly due to this condition. Torticollis, which is a tightening/shortening of the neck muscles, is much more common and can be resolved with simple stretching exercises. Craniosynostosis, unfortunately, does not resolve on its own and must be repaired surgically. Left untreated, craniosynostosis leads to a permanently misshapen head, and sometimes may have cognitive effects as it constrains brain growth.

While single-suture synostosis is not associated with any known causative or clearly genetic factors, there are known receptors that contribute to the development of these early fusions. Our team is working to help determine the mechanisms of early fusion on a cellular and molecular level to identify potential alternative therapies or predictive markers to help guide management.

What Are the Treatment Options?

There are several surgical options depending on the involved suture, the patient’s age at diagnosis, and whether one or more sutures are involved. In younger infants with only one involved suture, an endoscopic procedure to remove the fused suture is followed by helmet therapy for several months. In older children, an open approach is required with remodeling of the skull during surgery, instead of with the use of a helmet after surgery. There also additional techniques involving the use of spring-assisted correction and modified open approaches depending on the involved suture, the degree of abnormal molding, and the age of the child, that are also available. Neurosurgeons and plastic surgeons work together during these procedures to ensure the best results.

While Dove will have no memory of this, we know her parents will. We wish the family the best, and hope for a speedy recovery.

For more, see A Parent's Guide to Craniosynostosis Surgery and Frequently Asked Questions About Craniosynostosis